The Laurel is one of the most significant and emblematic timepieces in the history of Seiko and Japanese watchmaking, to the extent that it has been awarded the certification of “Heritage of Mechanical Engineering” from the Japan Society of Mechanical Engineers.

Was the Laurel truly the first wristwatch produced by Seiko?

In this article, I will try to clarify the history of the Laurel, its introduction dates, and what actually was Seiko’s first wristwatch.

The origins of the Laurel

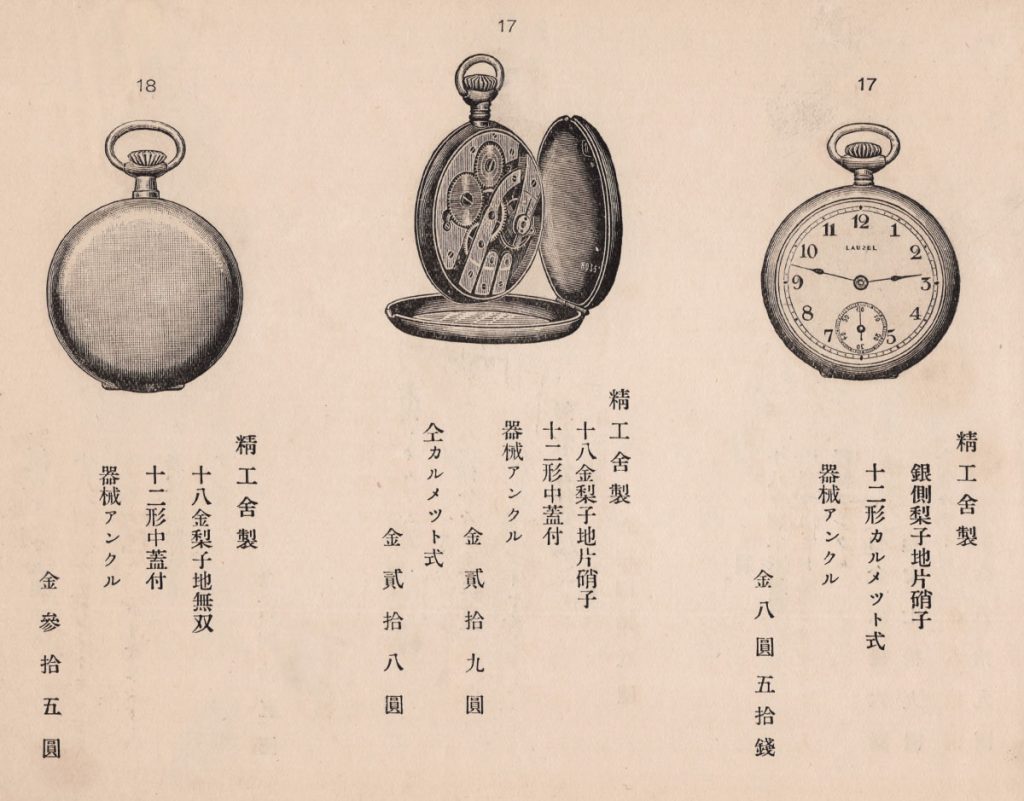

The Laurel was introduced as a pocket watch around 1913, and later converted into a wristwatch.

The first wristwatch version of the Laurel was introduced in 1915 under the alias “Lofty”.

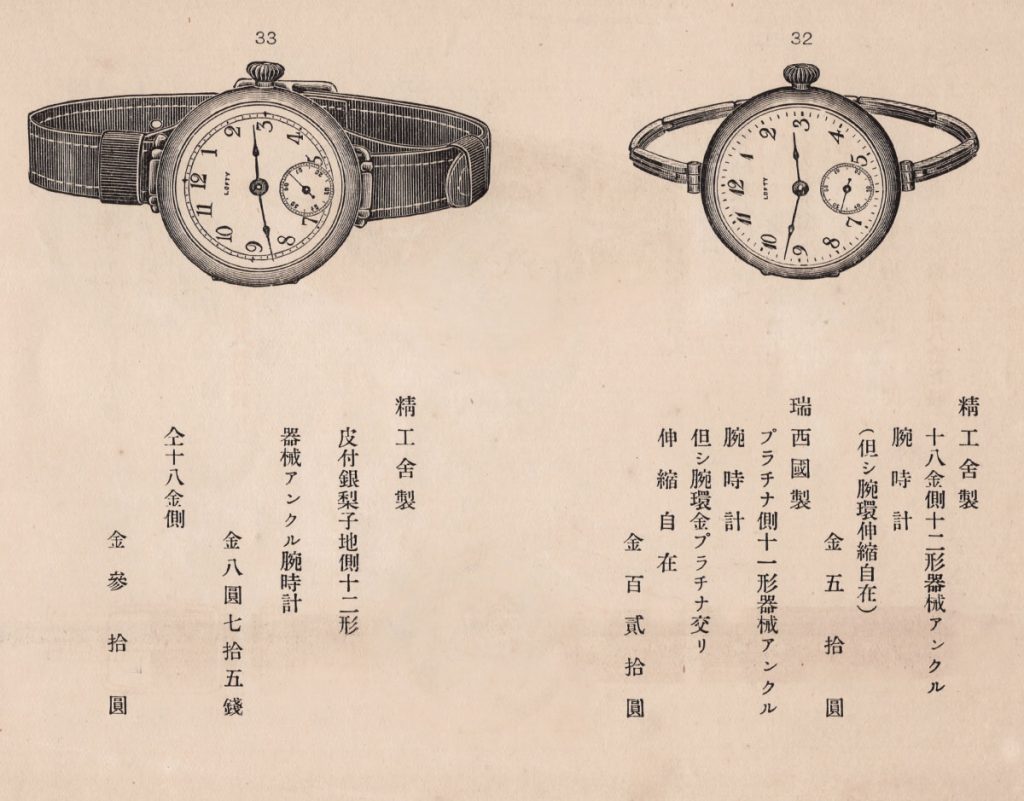

From the June 1915 catalog of the Hattori Watch Store:

Although the models in the 1915 catalog appear differentiated between Laurel (pocket watch) and Lofty (wrist watch), the Lofty alias seems to have been abandoned almost immediately: as early as 1916, even the wrist version began to be depicted in catalogs with the Laurel alias.

Moreover, in the brief period in which the Lofty alias was used, it can also be found on some pocket watch models, not exclusively wristwatches.

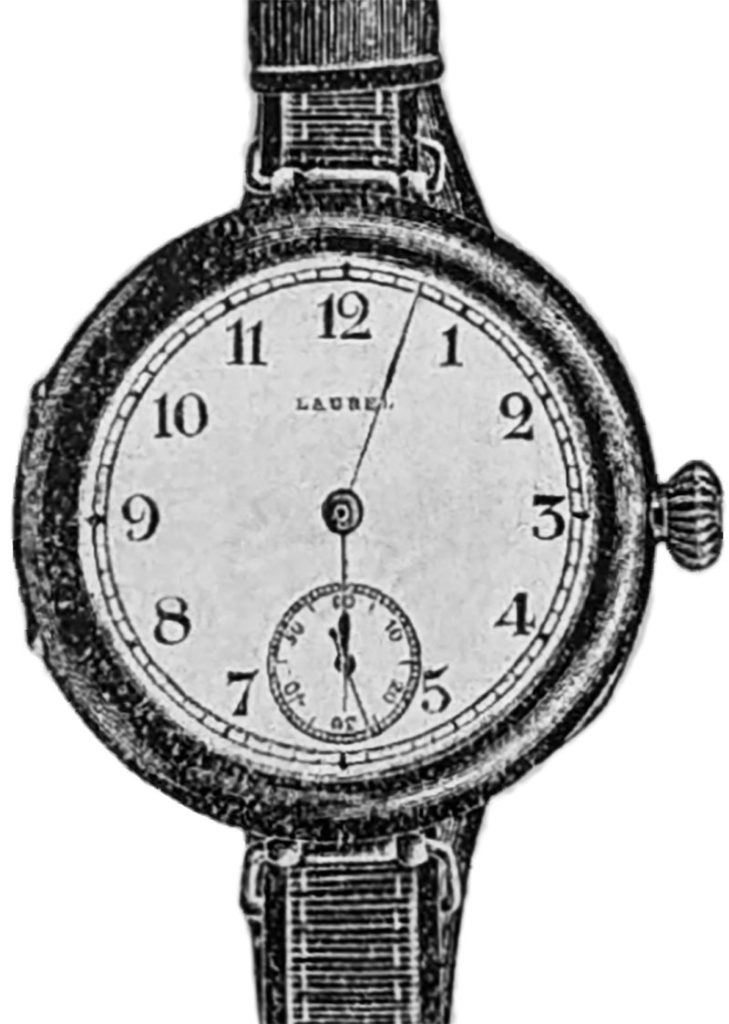

Laurel wristwatch from the 1916 Mitsukoshi catalog:

The first Seiko wristwatch

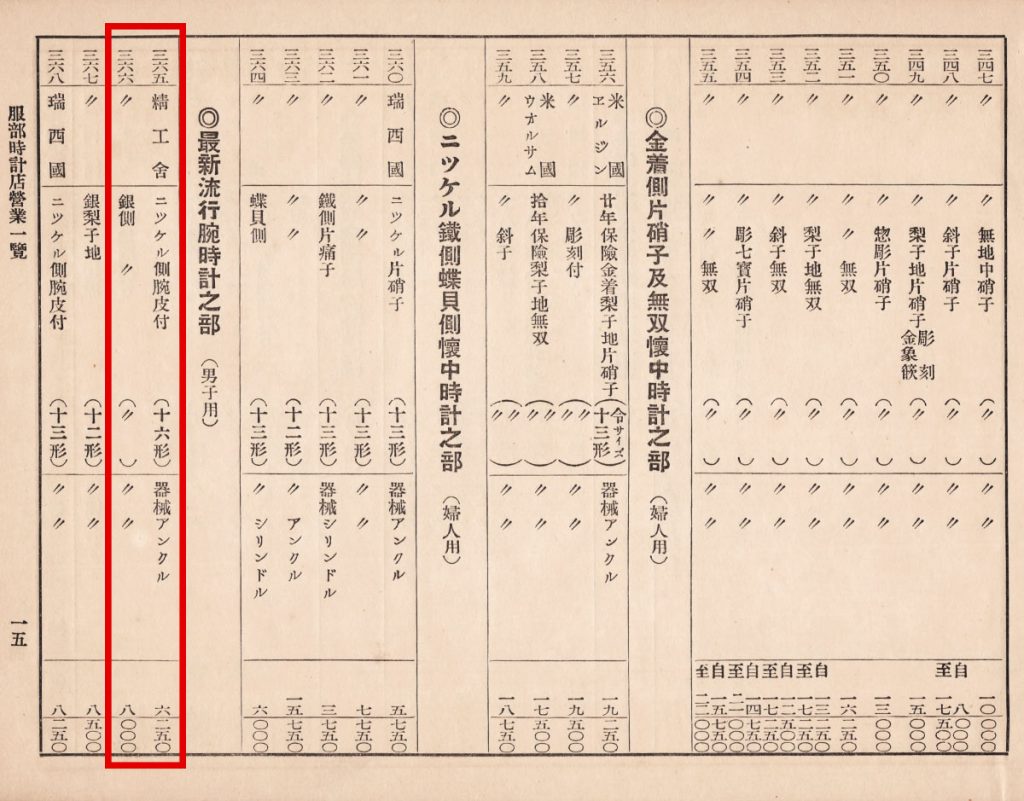

Although the Laurel has long been considered the first wristwatch produced by Seiko, period documentation shows that the 16-ligne Empire actually preceded it.

Empire (16-ligne):

introduced in 1909 as a pocket watch, converted into a wristwatch around 1913.

Laurel (12-ligne):

introduced around 1913 as a pocket watch, converted into a wristwatch in 1915.

In the book “Seikosha Pocket Watches” (精工舎懐中時計図鑑), the author Sadao Ryugo, who thoroughly investigated the subject, writes: “The price list from 1913 includes the Empire 16-ligne designed specifically for wrist use. The theory suggesting the Laurel wristwatch dates back to 1913 has been adopted due to some misinterpretation.”

Original text in Japanese: “また大正2年の定価表には、下図の16型エンパイヤ腕専用時計が掲載されています。 以上の事から、なんらかの解釈違いにより、ローレル腕時計大正2年説が採用されたと考えられます。”

Also in the 1915 Hattori catalog that I own, the 16-ligne wristwatch (Empire) is mentioned in the list of available models, with cases in silver and nickel.

From the documents of the time, it is therefore evident that the 16-ligne Empire was the first Seiko wristwatch, as well as the first to be produced in Japan. The wristwatch version of the Laurel was introduced about two years later.

Production at the Seikosha plant

The 12-ligne movement of the Laurel was small by the standards of the time, and its components were not easy to manufacture.

For this reason, its production posed a significant challenge. It seems that, at least in the initial phase, Seikosha craftsmen were only able to produce a few dozen units per day.

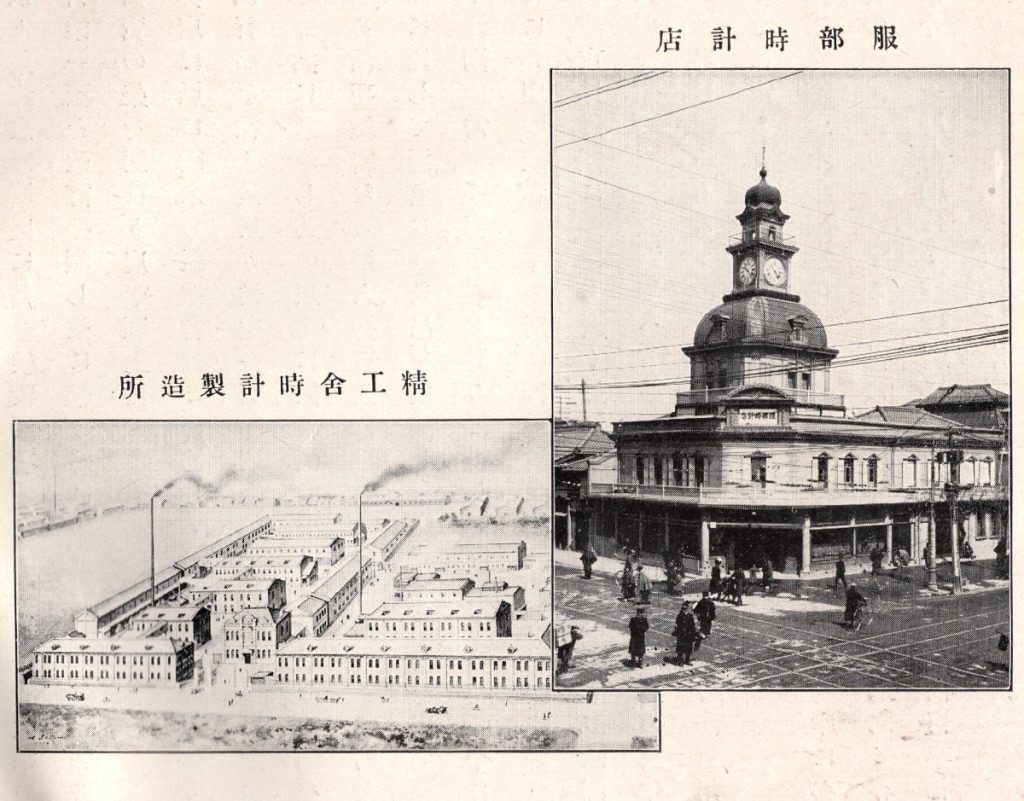

The Hattori watch store in Ginza and the Seikosha factory in 1915:

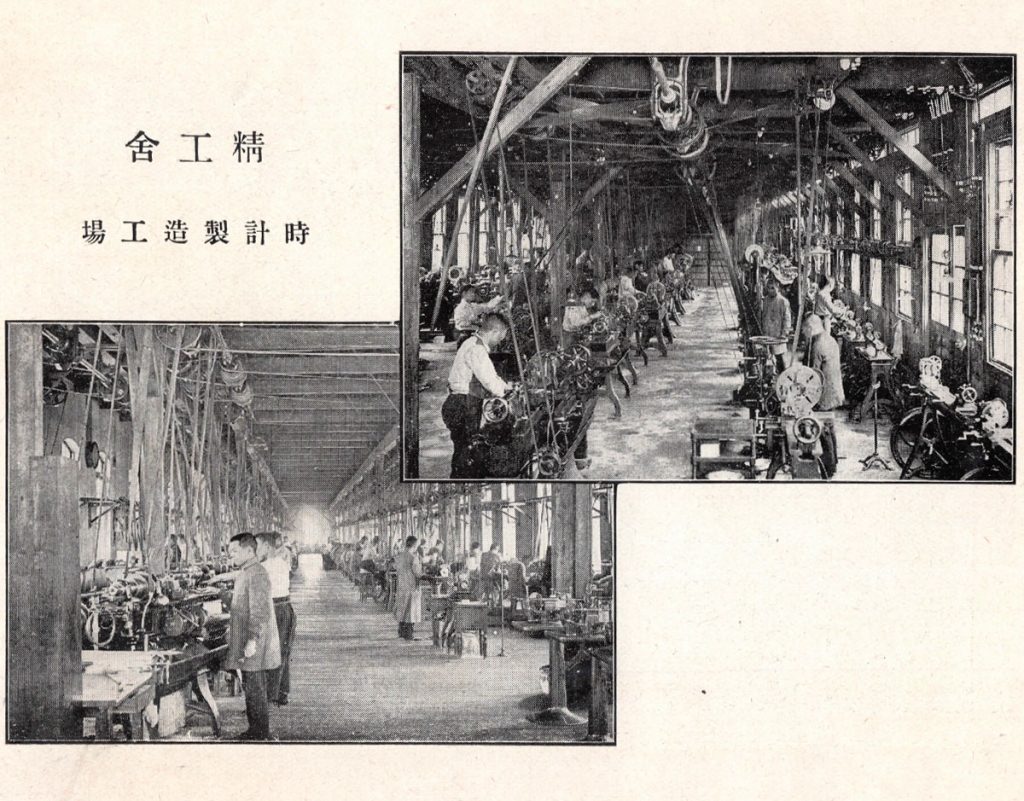

Craftsmen at work with machinery in the Seikosha plant:

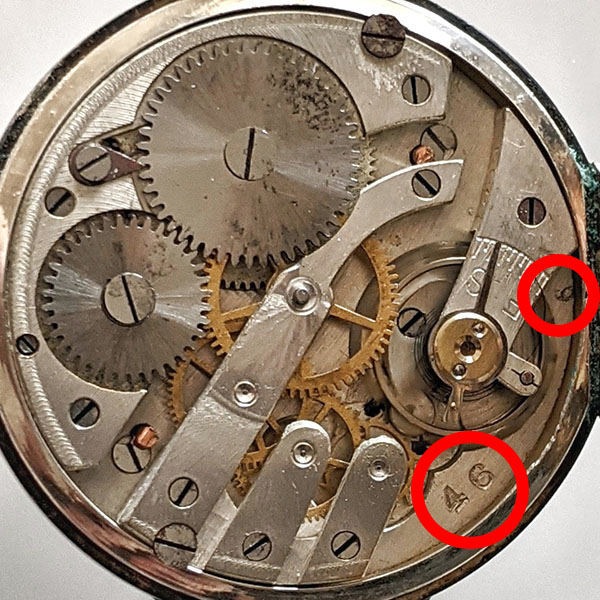

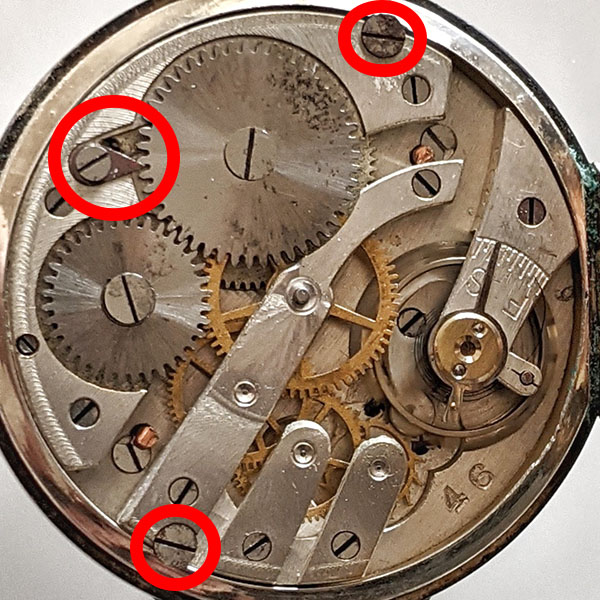

With the production techniques and machinery of the time, components from different Laurels often did not match each other.

To simplify the work, the main movement components were engraved with a number, and parts with the same number were drilled and assembled together.

Each movement was also engraved with codes identifying the craftsman and the production batch. In the following example, 46 is the production batch number, while 6 is the craftsman’s identification number.

When the Laurel entered production, Seiko had already achieved the capability to produce all watch components in-house, including enamel dials and balance springs.

However, it is not possible to determine with certainty that no imported or third-party components were used in the production of the Laurel.

The different versions of the Laurel

The production of the Laurel, starting from the introduction of the first pocket watch model, continued for at least a decade, during which several versions were produced, both pocket and wristwatches.

Various materials were used for the cases: 18 and 14 carat gold, silver, nickel, and shakudō, an ancient Japanese billon of gold and copper.

The dials were enameled, like most watches of that era. Enamel, similar to ceramic, is practically immune to the effects of humidity, and for this reason, some dials can still be admired in their original beauty.

The problem is that, over time and with shocks, the enamel can develop cracks, which are found on most existing specimens.

The most common case and dial configuration for pocket Laurels is that of the specimens shown in the following photos.

The following is a pocket Laurel with the same type of case, but made of shakudō, the ancient Japanese billon of gold and copper.

Hunter-type Laurel cases, characterized by a hinged cover protecting the front of the watch, are rarer and usually have the crown at 3 o’clock.

In the following photo, you can see the different movements of three hunter Laurels, in 18 and 14 carat gold, and in silver.

Some cases have a finish like the one shown in the following image.

Sometimes decorative images were also engraved, like those on the following specimens.

The first wristwatch models used a movable-lug case derived from pocket watches and very similar to that of the Empire wristwatch.

In the following photos, a 18 carat gold Laurel and a silver Laurel are depicted.

A more modern type of fixed-lug case was later adopted.

The following silver specimen, in addition to the Seikosha fan logo “SKS”, features the engraving of the Japanese character “賞” (Shō), symbolizing a prize or gift.

As can be seen from the presented specimens, there is some variety in the fonts used for the dials, and in some cases, the 12 o’clock index on wrist models was red, a detail that at the time represented a touch of style.

The movement of the Laurel

The structure of the Laurel’s movement is similar to that of some calibers produced by the Swiss company A. Schild, with which the Hattori group seemed to have agreements, probably similar to those made with the Moeris group.

The manual winding mechanical movement has a frequency of 18,000 bph and a diameter of 26.2 mm (12-ligne). Most specimens have 7 jewels, but some with 10 jewels exist, although extremely rare.

There can be various differences between the movements of different specimens, depending on the craftsman and the production period, and different levels of quality can be seen in the finishes.

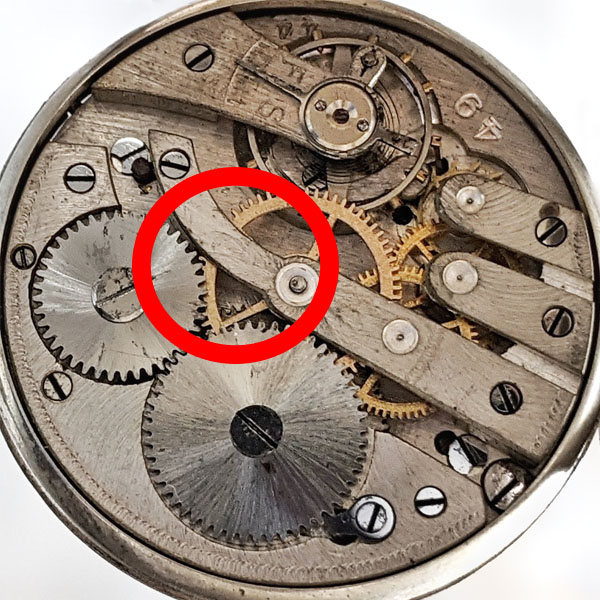

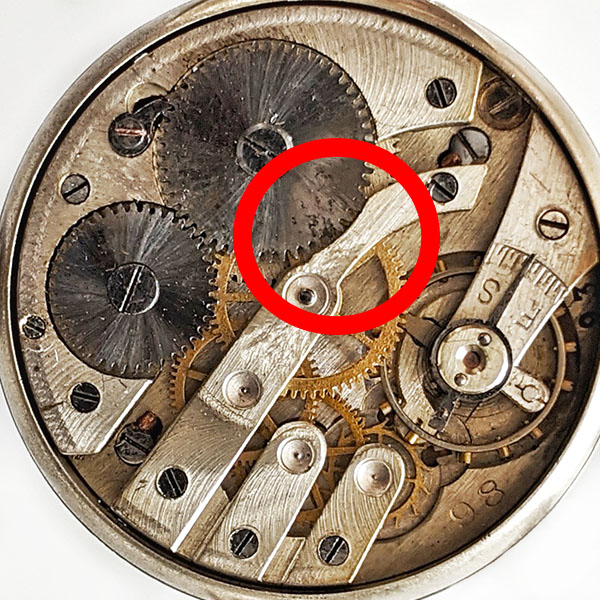

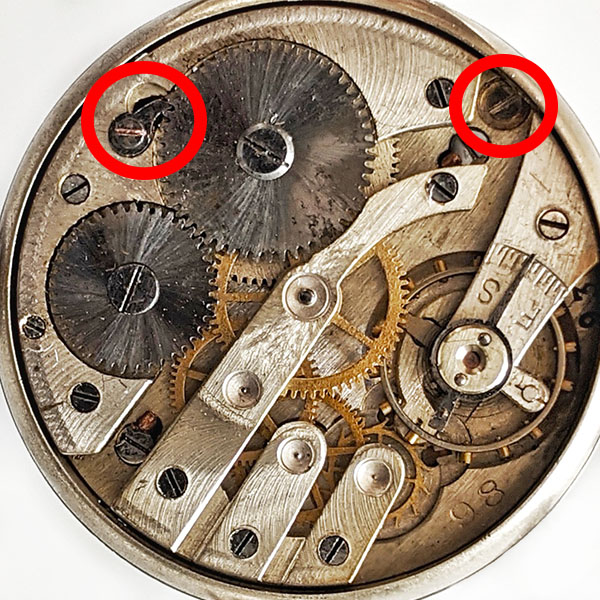

An immediately visible difference that separates almost all specimens with the crown at 3 o’clock from those with the crown at 12 o’clock is the appearance of the central bridge.

From the comparison, it can be seen that the original design was intended to have the crown at 12 o’clock, as moving it to 3 o’clock involved “cutting” part of the bridge in the center of the movement to allow repositioning of the crown wheel and the ratchet wheel.

In the following images, I have highlighted some of the other immediately visible and more common differences between various specimens: the position of the screws to fix the movement to the case and the shape of the ratchet.

Laurel in Seiko’s history

The production of the Laurel continued until the mid-1920s, but the alias was never completely abandoned by Seiko.

In the 1930s, other watches were produced under the name Laurel, based on Seiko-Moeris type calibers.

In the late 1950s, Seiko introduced an entire series of watches called Laurel, characterized by a caliber very similar to that of the Marvel but less refined and in a lower price range.

Within this series, the Laurel Alpinist, the first model of the historic Seiko Alpinist line of sports watches, was launched in 1959.

Another more recent series worth mentioning is that of the mechanical 4S Laurel watches, introduced in the 1990s.

Within the 4S family, the Laurel with reference SCVM001 from the 2000 Historical Collection stands out.

Various other series of watches based on a variety of movements, both mechanical and quartz, are also added to these.